LA MALOCLUSION CLASE III ESQUELETICA GRAVE MEDIANTE ABORDAJE PRIMARIO DE CIRUGIA ORTOGNATICA: INFORME DE CASO

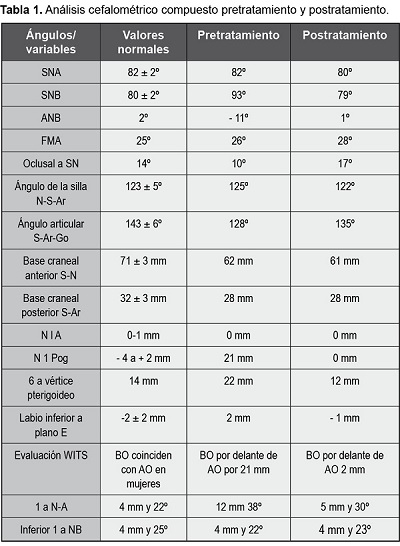

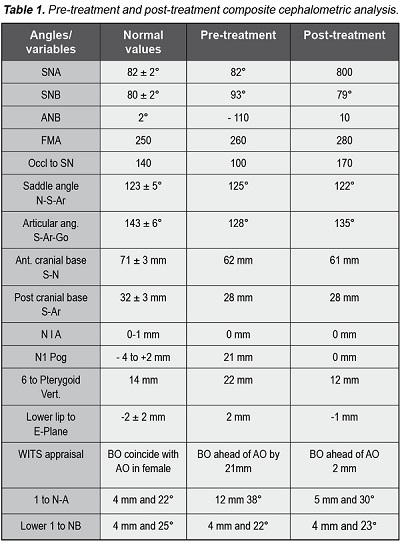

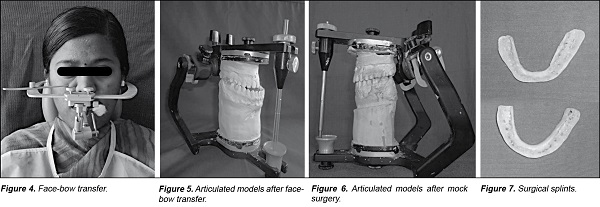

La maloclusión clase III es un problema de salud pública importante. El tratamiento de la maloclusión clase III esquelética grave en pacientes que no están en crecimiento, requiere una cirugía ortognática planificada de forma apropiada y bien ejecutada, por un equipo de al menos un ortodoncista y un cirujano maxilofacial. Para estos casos, existen dos enfoques para la cirugía.

Institución del autor

Swami Vivekanand Subharti University, Meerut, India

Coautores

Sridhar Premkumar* Marcos Roberto Tovani Palone**

Tamil Nadu Government Dental College, Chennai, India*

University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, Brasil**

Primera edición en siicsalud

22 de octubre, 2021