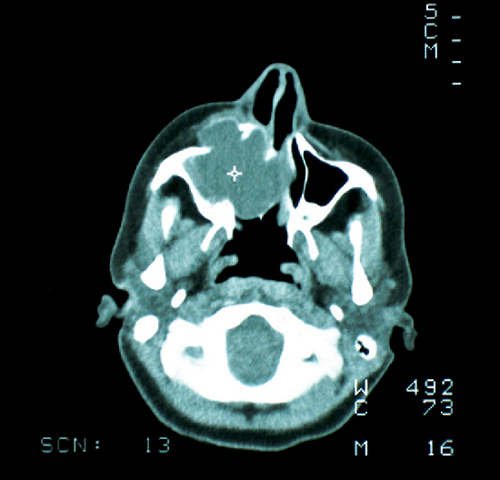

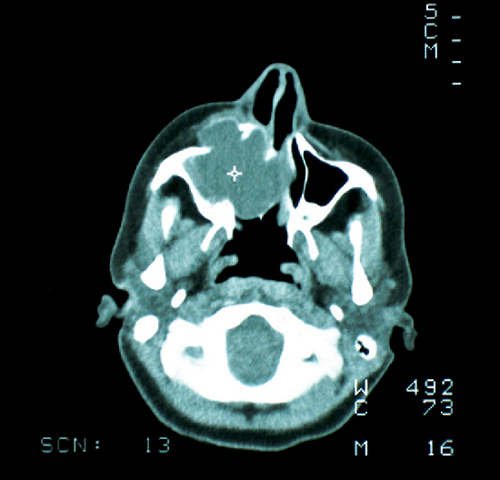

Figura 1. Tomografía axial computarizada en la que se observa el tumor y la destrucción de las paredes lateral y medial del seno maxilar.

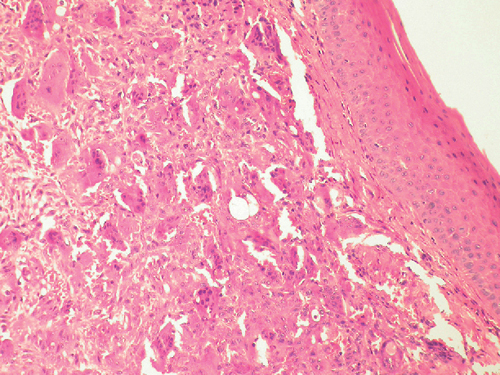

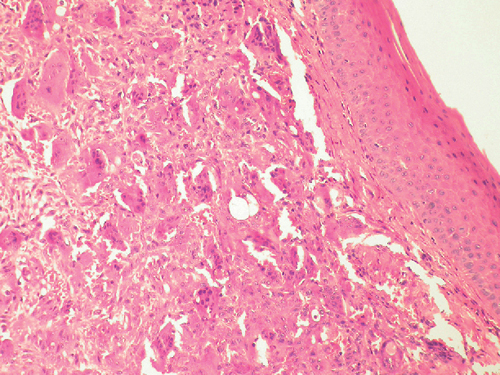

Figura 2. Microfotografía de mediano aumento en la que se observan numerosas células gigantes en un estroma celular fibroso (tinción con hematoxilina y eosina).Discusión

Figure 1. Axial CT scan depicting the tumor and destruction of the lateral and medial walls of the antrum.

Figure 2. Medium power micrograph showing numerous giant cells in a cellular fibrous stroma (H&E).Discussion

Copyright siicsalud © 1997-2025 ISSN siicsalud: 1667-9008